It's little surprise if we bring this same view to the beach. Our grasp on time is framed by the Victorian house overlooking the dunes, the rotted pilings from some forgotten pier.

Yet, in reality, we're standing on one page of a story that stretches back, and back, and back to the uttermost past. Literally. The sand that makes up Bay View beach, Saco, Maine began life about 600 million years ago. This is a brief story of one grain of that sand.

600 million years ago, North America was a different place, a young continent named Laurentia (or the non-poetic "North American Craton").

|

| I bet coastal Kentucky was lovely |

600 million years ago, a grain of quartz eroded out of the exposed face of a vanished granite hillside, and was washed downward by a vanished river. When it finally reached the Iapetus Ocean (the precursor to our modern Atlantic), it settled down to the sea-floor and was buried by other sediment. There it lay for millions of years, buried & compacted, becoming chemically attached to other grains around it, forming a sandstone.

By 500 million years ago other lands were converging on Laurentia. The Iapetus Ocean was shrinking & dying, succumbing to plate tectonics forcing continents together. 450 million years ago, volcanic islands off Laurentia's east coast were squeezed back onto the coast, an event called the Taconic orogeny. Our little grain of sand was swept up in the fury, as the stone it lay in bent, buckled, and shot upward out from under the disappearing sea. Over the next 200 million years, more and more islands, mini-continents, and even supercontinents crashed into Laurentia, crushing the old offshore sandstones & mudstones together. This was the birth of the Appalachian Mountains, and the birth of Maine as an above-ground landmass.

By 250 million years ago, all the continents of the world were welded together into one land, Pangea.

|

| Know how Africa & S. America look like jigsaw puzzle pieces? There's a reason! |

Slowly, over millions of years this overburden eroded away, running down other vanished rivers. Where did all that sediment go? Into the newly born Atlantic Ocean! ~200 million years ago, the forces that pulled the continents together now ripped them apart. North America broke free from Europe & Africa, and the Atlantic was born. Our tiny grain of sand now lay 150 miles away from Maine's brand-new coastline, still trapped high up in the towering Appalachians.

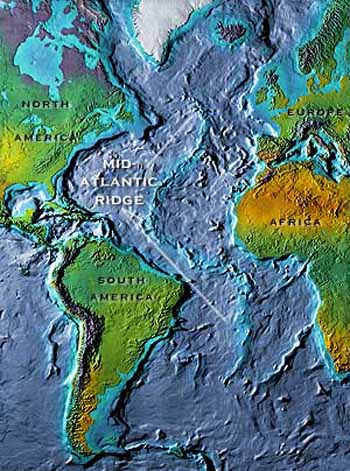

(The Atlantic Ocean is still widening today. Every year Maine gets about an inch further from Europe, thanks to the action of the mid-Atlantic Ridge.)

|

| The Atlantic Ocean - work in progress |

Glaciers aren't static, silent blocks of ice. With their terrible weight, they move, grind, torture, and pulverize the rocks beneath them. This last glacier rode up and over the denuded mountain holding our sand grain. And it ground it down. As it ate its way across the surface, it finally freed our grain of sand. It then moved the sand down and down, south & east. When the glacier finally receded 10,000 years ago, it left the sand grain on lowlands 50 miles west of the coast in a mass of clay, boulders, and debris a tenth of a mile deep.

Since then, the Saco River has been slowly eroding away the banks of all this debris, washing it down to the Gulf of Maine. Eventually -- maybe 5000 years ago, maybe last year -- the grain of sand fell out of the eroded rubble bank, plunged into the Saco River, and rolled & bounced its way the last 50 miles to the ocean. The ocean then churned & tossed it up onto Bay View beach. Where I scooped it up in my hand last week. Along with 10,000 other grains that all have their own tale to tell.

Wow, Harry! I read this earlier and thought it was way over my head, but I came back again and read it and was able to get it. I thank you for the education and simply beautiful ending. I couldn't agree more! Kate

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you enjoyed it! I'm new to geology myself, so I'm learning as I go. But I find it all so amazing. There's a beach about a half-hour south of us with these huge lumpy tortured rocks sticking up out of it. You can see the different layers in them, all bent and curved. The forces that can do that -- it all just kind of blows me away.

ReplyDeleteHi nice reading yyour post

ReplyDelete